Everything You Need to Know About the UX of Marketing Websites

Well, maybe not everything. But the themes below come up the most when we conduct user research for our clients. If you’re leading a team that is conducting a redesign, I hope these tips help you make the most of your marketing budget.

Key takeaways:

If you were to take away everything else on the page, a user should be able to get the gist of the website using the: primary navigation, headings and subheadings, calls-to-actions, and the footer.

If you wouldn’t do the behavioral equivalent of it in the real world, don’t do it on your website.

When you are approaching something in a new way, potentially violating your user’s established mental models, you run of risk of users being confused. The idea should have some grounding in user research and should be tested with users before and after launch.

In general, engagement means the user does something that moves you closer to your business goals. It often requires you to triangulate data from analytics and user research to identify the behaviors that signal engagement for your target audiences.

All of the things listed above require user research. A little goes a long way to avoid wasting time and money.

Understand how people navigate marketing websites

When someone lands on your website, they have a goal in mind. They are not on your website to kill time (usually). They want to get in, accomplish their task, and get out. If you think about your own behaviors, you’re the same way. And anything that stands between you and your goal—like a newsletter signup that takes up the entire browser—is unwanted and annoying.

As the page loads, your user is looking for clues to answer, “where am I? Can I accomplish my task here?” They rely on the primary navigation to determine what your organization does and what they might be able to do on the website. They also look for visually-prominent cues—headings and calls-to-action, for example—that hint that they are on the right path. Xerox PARC researchers refer to this as following the “information scent.” As long as a user feel like they are on the right path—that the information scent is strong—they’ll continue on the hunt. Once the scent is lost, they’ll backtrack or leave the website altogether.

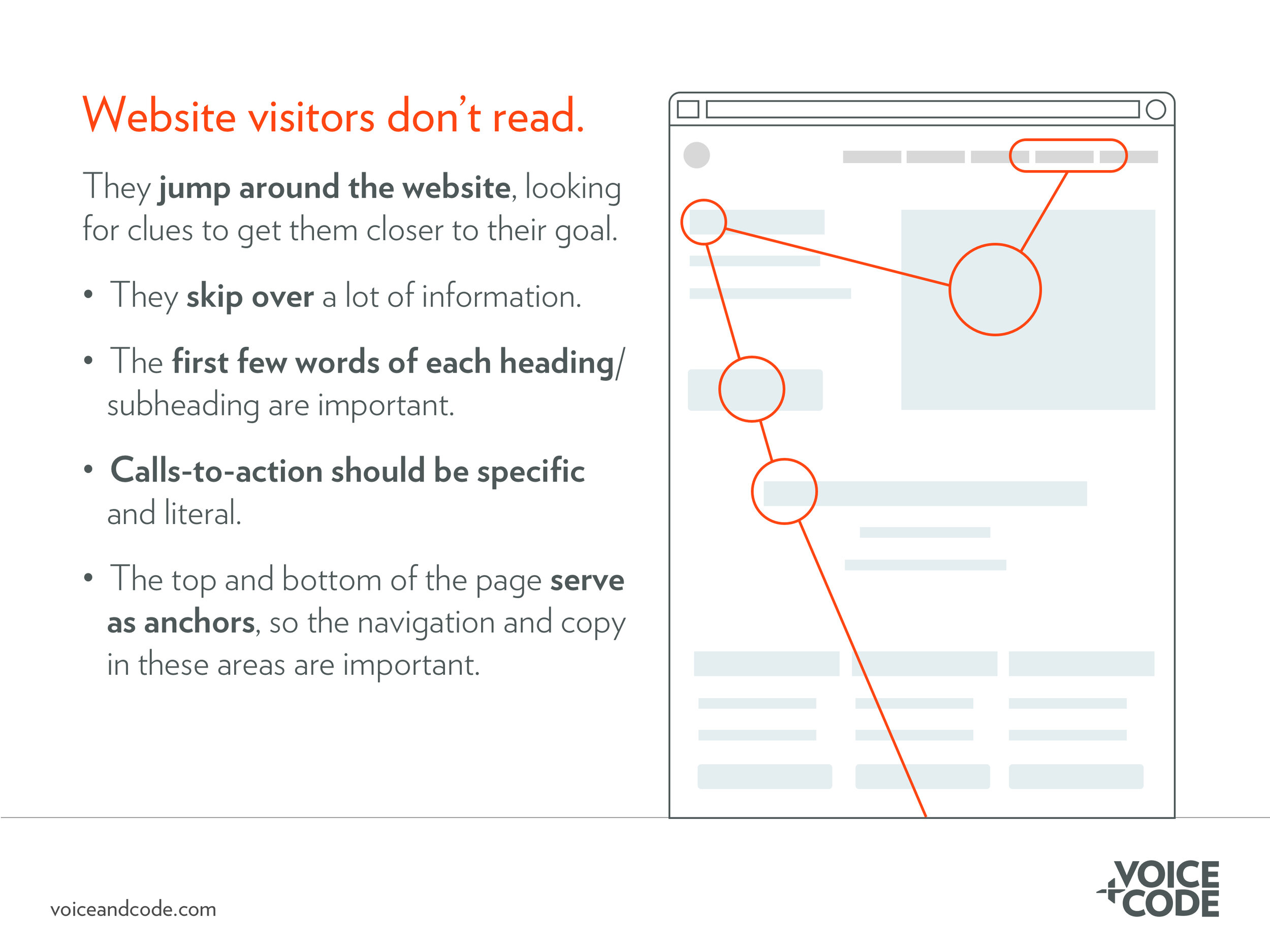

Now, it would be much easier to communicate to users if they actually took the time to read all the information on the page. But they don’t. Instead, they jump from one visually-prominent area to the next. These are the “animal tracks” they find on the path to decide if they should continue moving forward or not. Because of this, you should be paying particular attention to how these items are labeled and designed.

Usually, these areas of the page are:

The primary navigation

Headings and subheadings. In particular, the first few words.

Calls-to-action

The footer

If you were to take away everything else on the page, a user should be able to get the gist of the website using the information listed above.

People don’t read—they jump around the page looking for clues to get them closer to their goal. They skip over a lot of information, focusing instead on visually prominent pieces of information. They often use the primary navigation and footer as anchor points.

Establish digital relationships the same way you would in the real world

Marketing websites with poor user experiences expect to form relationships far sooner than we do in the real world. These behaviors end up deterring website visitors. Imagine if someone jumped in front of you the moment you entered a retail store, barring your entry, and asked you to sign up for their newsletter. Not cool. People don’t like these types of behaviors in the digital space, either.

If you wouldn’t do the behavioral equivalent of it in the real world, don’t do it on your website. Fostering and maintaining relationships is a long game—whether offline and online. Through user research, you should have developed a handful of personas who represents the target audiences of the website. When redesigning the website, carefully think about:

What are the user’s goals, motivations, and behaviors? How can we leverage these to make the most of their time here?

What outside factors should we take into account that might affect the how they use the website?

What’s the most important information the user needs to walk away with?

How should they feel?

What language will be the most effective?

What follow-up questions can we anticipate or objections we can prepare for?

How can we be most helpful?

When a redesign is starting to go down the track of relying on the someone’s personal preferences or violating how we establish relationships, I find that asking these types of questions tends to get people on the right track.

If your team is referring to a feature as “new and cool,” it definitely needs to be tested with users.

Remember that users are pulling from their experiences with other websites when they visit yours. Understanding where your users spend most of their time online will help you understand what they will expect from your website—a place where they are probably spending a very small percentage of their time overall. It’s also important to note that your users are not always as technically savvy as you are. While you and your team might think a feature is easy to use, your users might not.

So, when you are approaching something in a new way, potentially violating your user’s established mental models, you run of risk of users being confused. That’s not to say you shouldn’t incorporate new solutions. Just make sure they:

Have some grounding in user research.

Be usability tested with users during and after the design and development phase.

Let me be clear. You’re not asking users to dictate what features you should build. Instead, you’re leveraging research around their existing behaviors, frustrations, and needs and building a solution based around that. Then, you’re validating that solution both before and after you ship the final product. This will prevent you from wasting resources building things that no one cares about or can’t figure out how to use.

If you want to increase “engagement,” make sure you define what engagement means

When we ask clients what their goals are for their marketing website redesign, they almost always say they want to increase engagement. The problem? They can’t define what engagement means for their audiences. In general, engagement means the user does something that moves you closer to your business goals.

It often takes multiple website visits for users to do things that marketers typically want the most, like signing up for a newsletter or making a purchase. Because of this, you’ll need to define some smaller wins that point to the likelihood of continued or ramping up of engagement. These insights are typically a result of triangulating data from analytics (what are the commonalities of users who do end signing up for the newsletter?) and user research (what content or features can we develop that will be most interesting or valuable?). Our clients that have had the most success with this have developed key personas, scenarios (reasons users go to the website), and user journeys that highlight pain points and opportunities. The combination of these research artifacts bring to the light behaviors, motivations, and goals that often point to the behaviors that indicate engagement. Or it gives us the insights to build a new feature that would encourage engagement.

What do all of these insights have in common? They require user research.

Conducting user research at the beginning of the project and validating your ideas throughout the redesign is the best way to maximize the resources you have devoted to the project. How does this save you time and money? Here are just a few reasons:

You have a clear path for moving forward based on research—not guessing.

You’ll spend less time arguing about personal preferences. All you need to point to is the documentation around your user.

You’ll reduce the likelihood of developing features and content that are confusing or not used at all. And the money that you’ll eventually need to spend to fix them.